|

|

|

Excursions into Full Size

The

decade I spent with 4x4s was started by a holiday in Iceland in 1982

and a desire to go back for longer to explore more of the interior of

the country. Hiring a 4x4 in Iceland on that first holiday

had

shown that for a longer trip it would be cheaper to take my own vehicle

across on the ferry, so I purchased my first Land Rover. Like

many I thought that Land Rovers were indestructible and lasted forever,

a fact which was proven wrong when the Series III was found to need

some serious work including a new chassis. During the

year it took me to completely dismantle it, weld a new chassis

from an ex army kit of parts, and then refurbish and reassemble the

vehicle I ended up joining the local Land Rover club.

Initially

the intention was to learn from them, but it quickly led to various

"off road" events that I found to be easily accessible to anyone with a

4x4, and I was soon hooked on the activity of 4x4 trials. The

decade I spent with 4x4s was started by a holiday in Iceland in 1982

and a desire to go back for longer to explore more of the interior of

the country. Hiring a 4x4 in Iceland on that first holiday

had

shown that for a longer trip it would be cheaper to take my own vehicle

across on the ferry, so I purchased my first Land Rover. Like

many I thought that Land Rovers were indestructible and lasted forever,

a fact which was proven wrong when the Series III was found to need

some serious work including a new chassis. During the

year it took me to completely dismantle it, weld a new chassis

from an ex army kit of parts, and then refurbish and reassemble the

vehicle I ended up joining the local Land Rover club.

Initially

the intention was to learn from them, but it quickly led to various

"off road" events that I found to be easily accessible to anyone with a

4x4, and I was soon hooked on the activity of 4x4 trials.Trials simply involved the organiser in hiring a suitably rough venue such as a gravel pit, and then setting out several different sections each comprising a series of gates which the vehicles had to pass through without ever ceasing to move forwards. The trick in course setting was to create a course that only the best could complete by using the terrain to make the route difficult. In its simplest form there were only two classes, one for non road going vehicles which were as extreme as anyone wanted, and the other for road legal vehicles. So the Land Rover that had been purchased to visit Iceland instead found itself being used for commuting in the week and then being thrashed off road at weekends. Although the drivers ability played an enormous part in how the vehicle coped with crossing ground intended to stop it, the vehicle also had a large part to play and raw horsepower really helped. So like many others I started on the path of modifying vehicles and eventually building them from scratch. As I only had a 12" hacksaw, a 1/2" capacity electric drill, a large assortment of spanners / sockets, and a MIG welder it took considerable time to cut and shape enough metal to build a whole vehicle. The one in the photo on the left took almost two years to build. Combining a Land Rover Series I body onto a shortened Range Rover chassis and using the Rover V8 engine resulted in a pretty potent hybrid off road vehicle, although it could be a real handful on wet tarmac. The photo shows the hybrid on its first ever outing when I was in charge of setting out the sections. In the photo I had intended to take the section towards the distance but the vehicle became stuck. Once towed out I tried again turning towards the camera and managed to keep driving, so that "gate" of the section was set. Sharing the course setting with a friend meant that we had two Land Rovers to use, and could recover each other when stuck, but between us we broke three differentials in a single day of course setting. Thankfully we were already adept at replacing them "in the field" with a rear differential change taking well under an hour. |

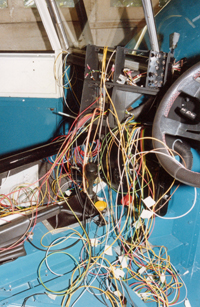

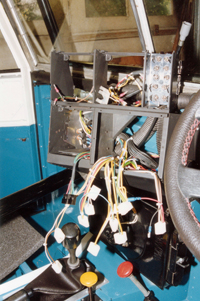

One

of the benefits of building your own vehicle was that you could

customise everything you wanted, and this hybrid ended up with a rather

special instrument and switch cluster as opposed to the normal spartan

Land Rover item. The vehicle also needed to have a complete

wiring loom created for it, which with additional electric radiator

cooling fans and extra lighting was quite complex. These two

photos show the mass of wires needed for the instrument console before

and after their incorporation into the wiring loom. The

"Achilles

heel" differentials were fixed by a friend who designed and produced a

special bronze block to stop the crown wheel and pinion from moving

apart under shock loads (which was what caused the differentials to

break), and he quickly convinced me to remove the 5 speed manual

gearbox in favour of a 3 speed automatic unit. In that form I

used the vehicle not only for the trials competions, both the road

going and extreme forms, and also used it for the "flat out" cross

country races strangely called "competitive safaris". This

was

where the automatic gearbox really came into its own as the driver

could keep both hands on the steering wheel while hurtling across the

rough terrain, and even shift down while at high speed on the flatter

bits in the knowledge that the gearbox wouldn't actually change gear

until the speed had dropped as you slowed for a slow bumpy bit of the

course. For a year I was really enjoying myself, but then a

simple one line rule change meant that the hybrid was no longer

eligible for many of the events I liked, so it was sold on and I had to

find another vehicle to play with. One

of the benefits of building your own vehicle was that you could

customise everything you wanted, and this hybrid ended up with a rather

special instrument and switch cluster as opposed to the normal spartan

Land Rover item. The vehicle also needed to have a complete

wiring loom created for it, which with additional electric radiator

cooling fans and extra lighting was quite complex. These two

photos show the mass of wires needed for the instrument console before

and after their incorporation into the wiring loom. The

"Achilles

heel" differentials were fixed by a friend who designed and produced a

special bronze block to stop the crown wheel and pinion from moving

apart under shock loads (which was what caused the differentials to

break), and he quickly convinced me to remove the 5 speed manual

gearbox in favour of a 3 speed automatic unit. In that form I

used the vehicle not only for the trials competions, both the road

going and extreme forms, and also used it for the "flat out" cross

country races strangely called "competitive safaris". This

was

where the automatic gearbox really came into its own as the driver

could keep both hands on the steering wheel while hurtling across the

rough terrain, and even shift down while at high speed on the flatter

bits in the knowledge that the gearbox wouldn't actually change gear

until the speed had dropped as you slowed for a slow bumpy bit of the

course. For a year I was really enjoying myself, but then a

simple one line rule change meant that the hybrid was no longer

eligible for many of the events I liked, so it was sold on and I had to

find another vehicle to play with. |

For about six months I had owned

a Land Rover Discovery which was the

family vehicle in the week, but available as a tow vehicle to transport

the hybrid to the more extreme events some weekends. So after

a

couple of months looking at alternative hobbies the Discovery suddenly

found itself in my workshop being modified for some serious

off

roading (as well as being the family hack). This change also

coincided with a growing interest in long distance off road events, a

sort of amateur version of the very expensive Pars - Dakar rally.

As a result on the same day that the Discoveries one year

warranty

expired it found itself on the start ramp in Munich for the Munich to

Marrakesh rally, and for the next three weeks it clocked up a large

amount of miles in the Atlas Mountains and the Northern fringes of the

Sahara. The Land Rover dealer that I had purchased the

vehicle

from sponsored us, and provided a lot of spares on a sale or return

basis from which we only used three air filters (deserts are very

dusty), and thankfully the vehicle and crew returned unscathed from the

adventure. Driving fast off road and trials sections were all

familiar to me and my For about six months I had owned

a Land Rover Discovery which was the

family vehicle in the week, but available as a tow vehicle to transport

the hybrid to the more extreme events some weekends. So after

a

couple of months looking at alternative hobbies the Discovery suddenly

found itself in my workshop being modified for some serious

off

roading (as well as being the family hack). This change also

coincided with a growing interest in long distance off road events, a

sort of amateur version of the very expensive Pars - Dakar rally.

As a result on the same day that the Discoveries one year

warranty

expired it found itself on the start ramp in Munich for the Munich to

Marrakesh rally, and for the next three weeks it clocked up a large

amount of miles in the Atlas Mountains and the Northern fringes of the

Sahara. The Land Rover dealer that I had purchased the

vehicle

from sponsored us, and provided a lot of spares on a sale or return

basis from which we only used three air filters (deserts are very

dusty), and thankfully the vehicle and crew returned unscathed from the

adventure. Driving fast off road and trials sections were all

familiar to me and my  co-driver

but the desert dunes were new to almost everyone on the event.

If

you didn't go up them fast enough you ended up stuck on the top as in

the photo, so you needed to be fast enough to almost fly over the top.

But over do the speed and if the unknown descent was too

steep

you would be on your roof, or you may simply hit another vehicle bogged

down on the other side. Driving the dunes was very

exhilarating,

but probably the scariest off roading I ever tried. co-driver

but the desert dunes were new to almost everyone on the event.

If

you didn't go up them fast enough you ended up stuck on the top as in

the photo, so you needed to be fast enough to almost fly over the top.

But over do the speed and if the unknown descent was too

steep

you would be on your roof, or you may simply hit another vehicle bogged

down on the other side. Driving the dunes was very

exhilarating,

but probably the scariest off roading I ever tried.Back home the Discovery was then converted to use an automatic gearbox about a year before Land Rover would offer it as an option (thanks to the help of that differential fixing friend) and that proved a god send when commuting around the M25 car park (sorry, motorway) every day. It also really helped off road as you could use heavy left foot braking and lots of engine power together to act as a crude form of traction control and "hill descent" that so many 4x4s now have fitted. The end result was that the Discovery could often climb hills that others in manual gearbox vehicles couldn't. The other benefit when on the long distance events was that the driver didn't end up with a knackered left leg after the thousands of gear changes needed when driving all day off road. The photo on the left shows the discovery in its final event before being sold, this time descending a steep hairpin bend in the Massif Centrale region of France. Thankfully all the stickers always came off without any trace, so the vehicle with some of its more radical parts removed was eventually traded in (remarkably with only one small dent) for a more conventional family car. |

The

reason the Discovery could be sold was because my third custom built

Land Rover had finally rolled out of my garage. This was

definitely the best I had built, and had the same 100" wheelbase as the

Range Rover and Discovery that I had been so happy with off road

before. As Land Rover never sold 100" Land Rovers, and many

people at that time considered that wheel base to be the ultimate, the

100" Land Rover had an almost "cult" status about it.

I was

even more pleased when the International Off Roader magazine wrote a

two page article about it starting with the words "Is this the best

100" Land Rover in the country ?". The

reason the Discovery could be sold was because my third custom built

Land Rover had finally rolled out of my garage. This was

definitely the best I had built, and had the same 100" wheelbase as the

Range Rover and Discovery that I had been so happy with off road

before. As Land Rover never sold 100" Land Rovers, and many

people at that time considered that wheel base to be the ultimate, the

100" Land Rover had an almost "cult" status about it.

I was

even more pleased when the International Off Roader magazine wrote a

two page article about it starting with the words "Is this the best

100" Land Rover in the country ?".The list of custom features was very long. Cut 10" out of the middle of the chassis and body of a standard long wheel base Land Rover. Fit a slightly tuned 3.9 litre V8 fuel injected engine and "beefed up" 4 speed auto gearbox. Change the transfer box gear ratios to compensate for the larger diameter tyres so the gearing was more like a Range Rover. Fit a heavy duty centre differential. Fit modified prop shafts as the engine and gearbox were now fitted further back in the chassis. Change the rear axle to a Range Rover one to get disc brakes all round. Fit my friend's special differentials, and an air locking unit to the rear one. Fit spring steel half shafts (that friend again) so that they could "wind up" on landing after a jump and not simply snap. Uprate the suspension. Fit a full roll cage, and modify the back so that I could sleep in it on long distance events. Move the driver's seat (taken from a Toyota Celica for comfort) and the steering wheel 2 inches towards the centre of the vehicle (no clutch pedal in the way) to improve driver elbow room. Fit special wheels and off road tyres to get the best possible steering lock to get around tight corners. Redo nearly all of the wiring, and tweak the electronic ECU for the engine to run without the catalytic converter exhaust. Fit full harness seat belts, which also meant relocating the handbrake so the driver could reach it (and fitting electric front windows as he couldn't reach the winders when belted in). Fit a full spec Rally Trip Computer, rev counter (and compass). These are just the things I can remember, but the end result was my favourite off road vehicle, purpose built to fit me and do what I wanted. The photo shows the 100" Land Rover somewhere in the Pyrenees when we drove mostly off road all the way from close to the Atlantic, along the length of the mountains, to the Mediterranean. Sadly it was sold after only two years as the "green lobby" demonised 4x4s and the Health & Safety culture made it impossible to hire the gravel pits and quarries anymore in case someone sued the owners. For the last event I ended up driving 800 miles each way to the former East Germany for an event held by the German Land Rover Club. There we had three very good days of competition, and I won the road legal vehicle class that had attracted over 100 vehicles and drivers of all types from across Europe. It seemed like a fitting end to a decade spent with 4x4s, and although many people still enjoy the sport in the UK today I decided to move on to something new (and hopefully cheaper). |